FEATURE by Willard Manus

The Papadakis

family knows all about the expression, "Pier Nine brawl." Back

in 1902, Nikos Papadakis, the patriarch of the clan, emigrated from Greece

to the port town of San Pedro--which is to Los Angeles roughly what Piraeus

is to Athens--and fought for survival by opening a waterfront hotel-brothel-gambling

joint. That was followed by a stint as a bootlegger during the Prohibition

era, the profits of which enterprise were invested in San Pedro real estate,

including a taverna on Sixth Street, just a stone's throw from the docks.

Today the Papadakis Taverna is still in operation--one food critic called

it "the best Greek restaurant this side of Athens"--and Nikos'

descendants are still battling on the waterfront, this time with bureaucrats

and politicians, not stevedores and swabbies.

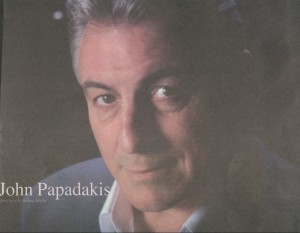

The fight, says John Papadakis (Nikos's grandson), "is over the future of San Pedro--the oldest settled community in California." Papadakis is the driving force behind an ambitious, billion-dollar development plan aimed at revitalizing largely run-down, blighted San Pedro by turning its eight-mile long harbor area into a "glittering, people-friendly waterfront gateway to Los Angeles."

The work of various city, state, cultural and business task forces, the L.A. Waterfront Development project is aimed at integrating San Pedro's maritime industrial past--San Pedro is one of the largest and busiest ports in the world--with accessible and thriving recreational, business and cultural amenities, thereby fostering economic progress for the entire community.

The first part of the project, the Cruise Ship Promenade, was completed in 2005. A walkway extending from the Vincent Thomas Bridge to the Federal breakwater, it affords pedestrians an up-close look at the giant ships calling on San Pedro. "People from all over southern California were recently able to enjoy the arrival of Queen Mary 2," Papadakis noted. "Because the proximity of the Terminal Island side creates the effect of a canal, one can almost reach out and touch the ships as they pass. That was a mind-blowing experience for the thousands who came to see the QM 2. Many of them came to my restaurant after the viewing and were ecstatic over the majesty of the ship, the grandness of it. These are the greatest things built in the world. They're larger than buildings and city blocks. They're an enormous attraction. Even our cranes are an attraction. We have a crane line. What we need is a skyline to go with it."

Here is where Papadakis' critics part company with him. Convinced that further exploitation of the waterfront would be an environmental disaster, they have presently blocked further development, pushing instead for open space, not commercial use of the harbor.

Papadakis scoffs at these detractors. "Technology is what helped clean our air with factory and automobile emissions; technology will solve our problems here. People who are truly concerned about pollution should be devoting themselves to technological solutions, rather than just calling attention to problems and using that as an excuse to hold everyone's future hostage here...It seems that some people are good at stopping things, but what have they genuinely offered to the community? What have they built, other than bitter criticism?"

Papadakis is no mere community gadfly. A born battler--he has his grandfather's genes, after all--he was a star football player in the early 70s at the University of Southern California, a 6-foot, 240-pound middle linebacker. "You can score a hell of a lot more on offense than you can on defense," he pointed out.

Papadakis is staying on the offense these days, fighting back against the obstructionists in San Pedro. Given his history and feisty nature, there is little chance he'll fail to reach his goals.