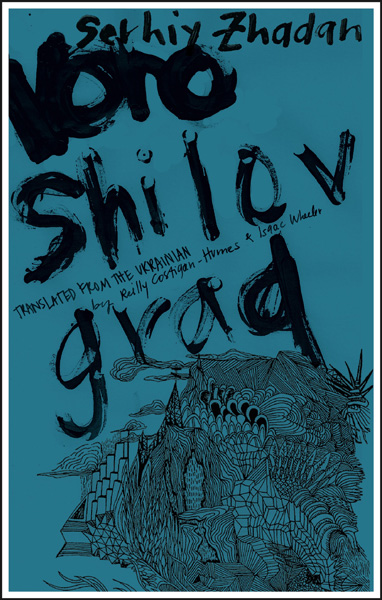

Voroshilovgrad

Deep Vellum

has also published another European literary gem, VOROSHILOVGRAD, by the

Ukranian Serhiy Zhadan (translated by Reilly Costigan-Humes and Issac

Wheeler). Zhadan is something of a rebel-hero in the Ukraine: besides

writing fiction and poetry, he sings in a rock band, translates foreign

writers and poets, and leads political protests (in 2014, he was assaulted

outside a government building in Kharkiv, an incident described in The

New Yorker.)

VOROSHILOVGRAD is set in a provincial part of the Ukraine, located near

the Russian border and the Carpathian Mountains. Its main city is Luhansk,

known as Voroshilovgrad in the Soviet era but now called by its original

name in an attempt to wipe out the recent past. But traces of that past

are to be found everywhere: in the ruins of abandoned factories and apartment

blocks, the shuttered schools and summer camps, the blighted roads and

fields–-and, especially in the minds and memories of the natives.

Life under the communists may have been difficult, but it was a life,

not the living death of capitalism.

What Henry Soros, who works in a regional government office (a front for

money-laundering, he admits), discovers when he returns to Luhansk to

help save the family garage is deeply unsettling. Local gangsters have

announced that they intend to take the business over, along with a nearby

disused air strip, as part of a plan to “develop the region”

by building an asphalt plant. Rather than deal with the Mafia, Henry’s

brother took off for Amsterdam, leaving behind his only employee, a mechanic

named Injured, to mind the store.

Injured and Henry are old friends, ex-teammates on a 1980s soccer team

that won a local championship. In their stubborn, proud, independent way

they refuse to give in to the Mafia and hand over what is a still-thriving

business, the last gas station for some hundred miles. Eventually, they

are joined in battle by a slew of their other soccer pals, a raffish bunch

that includes ex-prisoners, drunkards, con artists and smugglers. Bad-assed

as they are, they are a cut above the new generation, the “finance

pricks, pig cops, corporate shits, young lawyers, up and coming politicians,

analysts, business owners.” As one of them sums it up so succinctly,

“Fuck all those capitalists.”

The fight

to defend old-fashioned socialist honor, humanism and principles (flawed

as they may be) is just one of the book’s many storylines. Zhadan’s

canvas is large and is filled with bold characters: gypsies, Shtundists,

nomads, ghosts, refugees (“an inexplicable army”) from Mongolia,

Tibet, even Afghanistan. There are some powerful, sexy women as well,

plus an ex-drug-addict priest who delivers surprisingly intelligent sermons.

Zhadan also tosses into the mix fantastic and surreal flights of prose;

poetic descriptions of the still-beautiful parts of the Ukraine, with

its rich, black, enduring earth.

The last image in the book is of the priest, who while preaching to the

farmers about Daniel in the lion’s den “bends over to retie

his shoelace, straightens back up, lifts his hands to pray and exhales

a blue-pink tongue of flame, the fire of bittersweet joy.”